[Thanks to Insubria87 for this entry: His original post 'Early Celtic Presence in Northern Italy']

EARLY CELTIC PRESENCE IN NORTHERN ITALY

People of European History

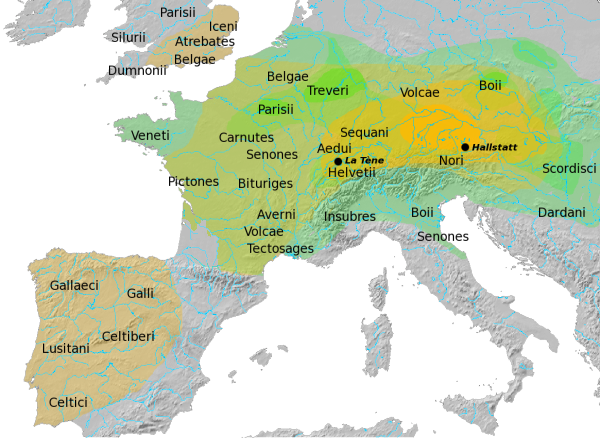

The Celts of the Latène age (475 to 20 BC) are named for the important archaeological finds at La Tène on the lake of Neuchâtel in Switzerland and are counted among the most important people of European history. Their central area of influence stretched from the Marne and Mosel, over southern France, and southern Germany, reaching to southern Poland and the Carpathians. The actual origins of the Celts is unknown. Myths and legends give a very contradictory picture.

Origins and Early History

Clear references to the history of the Celts are first found in the late Bronze age (the 13th century BC) with the beginning of the Canegrate culture. The name comes from the archaeological excavation at "Canegrate" (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canegrate) near Legnano north of Milan, where important finds were made. The Canegrate culture was founded by Celts who came from the Northwest alpine region and settled in the area between the Lake of Maggiore and the Lake of Como. They brought a language with them from which "Old-Celtic" continuously developed. They lived in direct proximity to the Golasecca-Celts of the Ticino (their name stems from the important archaeological finds in "Golasecca" at the place where the Ticino river flows out of the Lake of Maggiore) and the Helvetians in the north whose settlements reached far towards southern Germany.

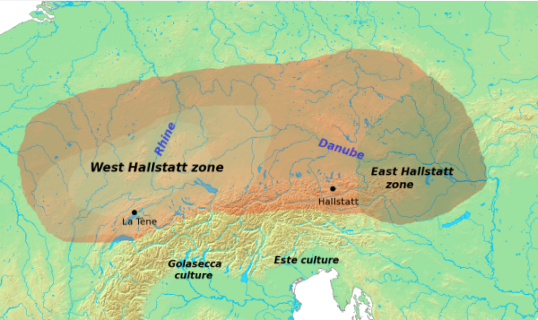

The Golasecca culture is a proto-historic pre-Celtic culture in northern Italy of which the type-site is Golasecca in the province of Varese, Lombardy (northern Italy). Sites characteristic of Golasecca culture have been identified in eastern Lombardy, Piedmont, the Canton Ticino and Val Mesolcina, in a territory stretching north of the Po River to sub-alpine zones, between the course of the Serio to the east and the Sesia to the west. The site of Golasecca, where the Ticino exits from Lake Maggiore, was particularly suitable for long-distance exchanges, in which Golaseccans acted as intermediaries between Etruscans and the Halstatt culture of Austria, supported on the all-important trade in salt.

In a broader context, the subalpine Golasecca culture is the very last expression of the Middle European Urnfield culture of the European Bronze Age. The culture's richest flowering was Golasecca II, in the first half of the sixth to early fifth centuries BCE. It lasted until it was overwhelmed by the Celts in the fourth century and was finally incorporated into the hegemony of the Roman Republic.

situation of the Golasecca culture to the south of the Hallstatt culture.

Golasecca culture is divided for convenient reference into three parts: the first two cover the period of the ninth to the first half of the fifth century BCE; the third, coinciding with La Tène A-B of the later Iron Age in this region and extending to the end of the fourth century BCE, is marked by increasing Celtic influences, culminating in Celtic hegemony after the conquests of 388 BCE. The very earliest finds are of the Late Bronze Age (ninth century), apparently building upon a local culture.[1]

Cremation near the burial site, followed by ash and bone burials in terracotta jars, in excavated pits set at determined distances one from the other in scattered necropolises, characterize a culture of many small village settlements.

In Golasecca culture some of the first evolved characteristics of historic society may be seen, in the specialized use of materials and the adaptation of the local terrain. The early-period habitations were circular wooden constructions along the edge of the river's floodplain; each was built on a low basement of stone round a central hearth and floored with river pebbles set in clay. Hand-shaped ceramics, made without a potter's wheel, were decorated in gesso. The use of the wheel is known from the carts in the Tomb of the Warrior at the Sesto Calende site. Amber beads from the Baltic sea across the Amber Road and obsidian reveal networks of long-distance trade. From the seventh century onwards some tombs contain burial goods imported from Etruscan areas and Greek objects[2]

The settlements depended on domesticated animals: remains reveal the presence of goats, sheep, pigs, cattle and horses. Some legume and cereal crops were cultivated; nuts and fruits were collected. The dugout boats from Castelletto Ticino and Porto Tolle are conserved at the museum of Isola Bella. Metal, though rare, was in increasing use.

Undeciphered written characters are found incised in ceramics or on stone.

The Golasecca culture is best known by its burial customs, where an apparent ancestor cult imposed respect of the necropoli, a sacred area untouched by agrarian use or deforestation. The early-period burials took place in selected raised positions oriented with respect to the sun. Burial practices were direct inhumation or in lidded cistae. Stone circles and alignments are found. Burial urns were painted with designs, with accessory ceramics, such as cups on tall bases. Bronze objects are usually of wearing apparel: pins and fibulas, armbands, rings, earrings, pendants and necklaces. Bronze vessels are rare. The practice of cremation persists into the second period (early sixth to mid-fourth centuries)

The old sites—Golasecca, Sesto Calende, Castelletto Ticino—maintained their traditional autochthonous character through the sixth century, when outside influences begin to be detectable. At the beginning of the fifth century, pastoral practices resulted in the development of new settlements in the plains.

The first finds were discovered at several locations in the comune of Golasecca in 1824, by the antiquarian abate Giovan Battista Giani, who identified the clearly non-Roman burials as remains of the battle between Hannibal and Scipio Africanus[3]. In 1865 Louis Laurent Gabriel de Mortillet, a founder of European archaeology, rightly assigned the same tombs to the early Iron Age. The modern assessment of Golasecca culture is derived from the campaigns of 1965-69 on Monsorino, directed by Mira Bonomi.

Lepontii

The Lepontii were an ancient people occupying portions of Rhaetia (in modern Switzerland and Italy) in the Alps during the time of the Roman conquest of that territory. The Lepontii have been variously described as a Celtic, Ligurian, Raetian, and Germanic tribe. However, most evidence, including recent archeological excavations, and their association with the 'Golasecca culture' of Northern Italy, indicates a Celtic origin although they might actually be an amalgamation of Raetians (who were of Etruscan origin) and Celts.

The chief town of the Lepontii was Oscela, now Domodossola, Italy, and their territory included the southern slopes of the St. Gotthard Pass and Simplon Pass, corresponding roughly to present-day Ossola and Ticino. See also: Lepontic language. This map of Rhaetia [1] shows the location of the Lepontic territory, in the south-western corner of Rhaetia. The area to the South, including what was to become the Insubrian capital Mediolanum (modern Milan), was Etruscan around 600-500 BC, when the Lepontii began writing tombstone inscriptions in their alphabet (one of several Etruscan-derived alphabets in the Rhaetian territory).

Lepontic is an extinct Celtic language that was spoken in parts of Rhaetia and Cisalpine Gaul (today's Northern Italy) between 700 BC and 400 BC. Sometimes called Cisalpine Celtic, it is considered a dialect of the Gaulish language and thus a Continental Celtic language (Eska 1998).

The language is only known from a few inscriptions discovered that were written in the alphabet of Lugano, one of five main varieties of Northern Italic alphabets, derived from the Etruscan alphabet. These inscriptions were found in an area centered on Lugano, including Lago di Como and Lago Maggiore. Similar scripts were used for writing the Rhaetic and Venetic languages, and the Germanic runic alphabets probably derive from a script belonging to this group.

Lepontic was assimilated first by Gaulish, with the settlement of Gaulish tribes north of the River Po, and then by Latin, after the Roman Republic gained control over Gallia Cisalpina during the late second and first century BC.

The grouping of all of these inscriptions into a single Celtic language is disputed, and some (including specifically all of the older ones) are said to be in a non-Celtic language related to Ligurian (Whatmough 1933, Pisani 1964). Under this view, which was the prevailing view until about 1970, Lepontic is the correct name for the non-Celtic language, while the Celtic language is to be called Cisalpine Gaulish. Following Lejeune (1971), the consensus view became that Lepontic should be classified as a Celtic language, albeit possibly as divergent as Celtiberian, and in any case quite distinct from Cisalpine Gaulish. Only in recent years, there has been a tendency to identify Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish as one and the same language.

While the language is named after the tribe of the Lepontii, which occupied portions of ancient Rhaetia, specifically an Alpine area straddling modern Switzerland and Italy and bordering Cisalpine Gaul, the term is currently used by many Celticists to apply to all Celtic dialects of ancient Italy. This usage is disputed by those who continue to view the Lepontii as one of several indigenous pre-Roman tribes of the Alps, quite distinct from the Gauls who invaded the plains of Northern Italy in historical times.

The older Lepontic inscriptions date back to before the 5th century BC, the item from Castelletto Ticino being dated at the 6th century BC and that from Sesto Calende possibly being from the 7th century BC (Prosdocimi, 1991). The people who made these inscriptions are nowadays identified with the Golasecca culture, which has been ascribed a Celtic identity (De Marinis, 1991). The extinction date for Lepontic is only inferred by the absence of later inscriptions.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lepontic_language

Ligures

The Ligures (singular Ligus or Ligur; English: Ligurians, Greek: Λίγυες) were an ancient people who gave their name to Liguria, which once stretched from Northern Italy into southern Gaul. According to Plutarch they called themselves Ambrones which means ¨people of the water¨. The Ligures inhabited what now corresponds to Liguria, northern Tuscany, Piedmont, part of Emilia-Romagna, part of Lombardy, and parts of southeastern France.

Classical references and toponomastics suggest that the Ligurian sphere once extended further into central Italy (Taurisci): according to Hesiod's Catalogues (early 6th century BC) they were one of the three main "barbarian" peoples ruling over the Western border of the known world (the others being Aethiopians and Scythians). Avienus, in a translation of a voyage account probably from Marseille (4th century BC) speaks of the Ligurian hegemony extending up to the North Sea, before they were pushed back by the Celts. Ligurian toponyms have been found in Sicily, the Rhône valley, Corsica and Sardinia.

It is not known for certain whether they were a pre-Indo-European people akin to Iberians; a separate Indo-European branch with Italic and Celtic affinities; or even a branch of the Celts or Italics. Kinship between the Ligures and Lepontii has also been proposed. Another theory traces their origin to Betica (modern Andalusia).

The Ligures were assimilated by the Romans, and before that by the Gauls, producing a Celto-Ligurian culture.

Tribes

Numerous tribes of Ligures are mentioned by ancient historians, among them:

The Ligurian language was spoken in pre-Roman times and into the Roman era by an ancient people of north-western Italy and south-eastern France known as the Ligures. Very little is known about this language (mainly place names and personal names remain) which is generally believed to have been Indo-European; it appears to have shared many features with other Indo-European languages, primarily Celtic (Gaulish) and Italic (Latin and the Osco-Umbrian languages).

Xavier Delamarre argues that Ligurian was a Celtic language, similar to but not the same as Gaulish. His argument hinges on two points: firstly, the Ligurian place-name Genua (modern Genoa, located near a river mouth) is claimed by Delamarre to derive from PIE *genu-, "chin(bone)". Many Indo-European languages use 'mouth' to mean the part of a river which meets the sea or a lake, but it is only in Celtic that reflexes of PIE *genu- mean 'mouth'. Besides Genua, which is considered Ligurian (Delamarre 2003, p. 177), this is found also in Genava (modern Geneva), which may be Gaulish. However, Genua and Genava may well derive from another PIE root with the form *genu-, which means "knee" (so in Pokorny, IEW [1]).

Delamarre's second point is Plutarch's mention (Marius 10, 5-6) that during the Battle of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BC, the Ambrones (who may have been a Celtic tribe) began to shout "Ambrones!" as their battle-cry; the Ligurian troops fighting for the Romans, on hearing this cry, found that it was identical to an ancient name in their country which the Ligurians often used when speaking of their descent (outôs kata genos onomazousi Ligues), so they returned the shout, "Ambrones!".

Delamarre points out a risk of circular logic - if it is believed that the Ligurians are non-Celtic, and if many place names and tribal names that classical authors state are Ligurian seem to be Celtic, it is incorrect to discard all the Celtic ones when collecting Ligurian words and to use this edited corpus to demonstrate that Ligurian is non-Celtic or non-Indo-European.

Strabo on the other hand states "As for the Alps... Many tribes (éthnê) occupy these mountains, all Celtic (Keltikà) except the Ligurians; but while these Ligurians belong to a different people (hetero-ethneis), still they are similar to the Celts in their modes of life (bíois)."

The Ligurian-Celtic question is also discussed by Barruol (1999).

Herodotus (5.9) wrote that sigunnai meant 'hucksters, peddlers' among the Ligurians who lived above Massilia.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligurian_language

No comments:

Post a Comment